INTRODUCTION

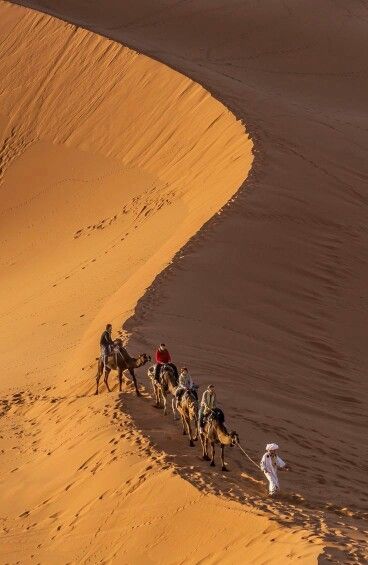

Libya’s independence in 1951 did not come only from negotiations or international decisions, it was shaped by deeper forces that had long connected the land and its people. One of the most overlooked of these forces is the caravan desert. This is a network of routes, movement, and exchange that linked Libya’s regions long before the modern state existed.

Understanding the significance of the caravan desert to Libya’s independence means looking beyond borders and capitals. It means recognizing how mobility across the Sahara created social ties between Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan, making unity possible in a territory often described as too large and divided to become a nation.

1. The Lifeline of Libyan Society

The caravan desert was the lifeline of Libyan society. Salt, dates, and gold moved along these routes, but so did ideas, customs, and religious practices. Traders and nomads fostered mutual dependency and trust among communities, creating a shared identity that transcended regional boundaries.

Cultural exchanges along these routes strengthen communal bonds. Poetry, oral histories, and religious teachings traveled alongside goods, especially through caravan hubs such as Ghadames and Fezzan, which served as key centers of exchange in the Sahara.

These movements embedded a sense of belonging and common purpose in a land that was geographically large and historically difficult to govern.

2. Enabling Social Services and Education Infrastructure Through Trading Lodges

The zawiyas (lodges) established along caravan routes provided essential social services that sustained Libyan communities during colonial occupation. The Mother Lodge of the Sanusi order served as a school, cultural and business center, religious chapterhouse, a refuge for the poor to seek food and shelter, and as a place of rest for caravan traders.

A typical Senussi zawiya included facilities for worship, classrooms for religious instruction, accommodations for students and travelers, storehouses for goods, and agricultural lands that provided economic support for the institution’s activities.

These multifunctional institutions preserved Islamic education and social cohesion when Italian colonial forces actively suppressed native institutions, creating autonomous spaces where Libyans could maintain their cultural identity independent of colonial control.

4. Supporting Resistance to Colonial Rule

Italy, and later Britain and France, struggled to control the interior regions of Libya. The mobility allowed by the caravan desert meant that colonial authorities could occupy coastal cities but not the desert interior, where trade and social networks continued. This created resilient communities that could maintain continuity and identity, ultimately making independence feasible.

The mobility inherent in caravan trade and nomadic pastoralism facilitated decentralized forms of governance, communication, and resistance in Libya. Nomadic and semi-nomadic populations like the Tebu and Tuareg maintained economies based on pastoralism and caravanning across large Saharan territories.

Local tribes continued fighting Italian occupiers for approximately 22 years , while kinship-based political and economic loyalties were strengthened due to weak centralized colonial institutions.

These decentralized networks allowed communities to preserve their social and economic structures during foreign occupation. Anti-colonial resistance movements emerged across Cyrenaica, Tripolitania and Fezzan since the Italian occupation began in 1911, contributing to the eventual formation of a unified Libyan state that gained independence on December 24, 1951. (Read more here)

4. Religious and Political Legitimacy for Independence Leadership

Caravan trade wealth provided the Sanussi order with the resources and legitimacy that directly translated into political leadership at independence. King Idris’s legitimacy as Libya’s first king was based on his leadership of the Sanusi Sufi order and unification of the struggle against Italian imperialism from 1911 to 1951.

By the turn of the 20th century, the Sanussi order used its religious lodges with the existing tribal system to such an extent that it was able to marshal its members against the Italians, and later emerged as political spokesmen for the people in negotiations leading to independence on December 24, 1951.

The economic power derived from controlling trans-Saharan trade routes gave the Sanussi movement both material resources and spiritual authority, positioning its leader as the natural choice to unite Libya’s diverse regions at independence.

5. Strategic Positioning and International Connections

Caravan trade routes positioned Libyan resistance movements to maintain international connections that supported independence efforts. Around 1856, the Sanusi order moved its headquarters to the oasis of Jaghbub near the Egypt-Libya border, whose position near caravan routes connecting Egypt, Libya, and Sudan allowed the Order to engage with trade networks and extend its influence southward.

During World War II, Idris al-Senussi initiated contact with British authorities from his exile in Egypt and organized the Libyan Arab Force that operated under British command, with these contributions acknowledged as supporting Allied victory and Libya’s path to independence.

The cross-border relationships established through caravan trade enabled Libyan leaders to secure external support, coordinate with allied powers, and ultimately negotiate the terms of Libya’s independence in 1951.

CONCLUSION

The caravan desert was an important instrument of Libya’s unity, resistance, and identity. Its social, economic, and cultural networks made independence possible, proving that nationhood was already alive in the deserts long before 1951. The significance of the caravan desert to Libya’s independence reminds Libya’s of it’s history of connection and resilience that predates colonial borders and continues to shape its national identity today.

Explore more stories about African countries on their independence days at Richlyafrican.org